All in the timing

There's an apparently-false story that occasionally makes the round among lefty circles that some branch of the US government kept a list of "premature anti-fascists" who opposed Hitler and Mussolini too early and too vehemently, making them suspicious in the eyes of the security state as likely communists.

While the story may be a more modern contrivance, it resonates because it underlines the political reality that the timing of one's positions can be as important as their substance.

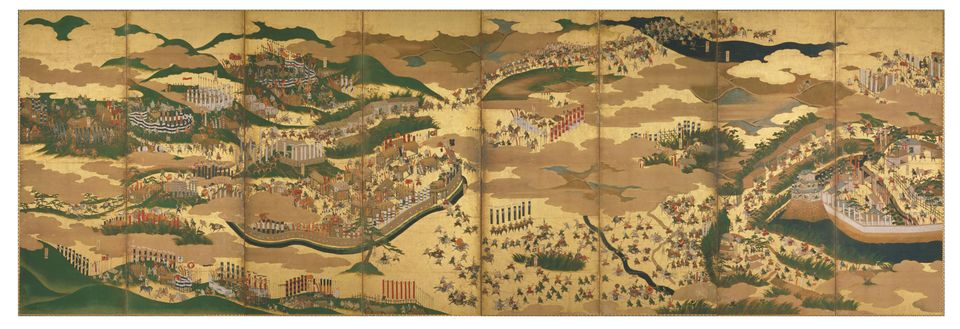

In 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu won the decisive Battle of Sekigahara, all but assuring that Ieyasu would conquer all of Japan and end the country's Warring States period. The resulting political order lasted 250 years, with Ieyasu's descendants ruling as de facto regents over the entire country.

To keep his many feudal vassals in line, Ieyasu established a clear pecking order, with the timing of a daimyō's (regional warlord's) declaration of allegiance to the Tokugawa cause determining the income and influence allotted to that daimyo:

- Ieyasu's family were at the top;

- Next were fudai daimyō, composed of Tokugawa vassals from before the war, as well as some other warlords who supported Ieyasu before the Battle of Sekigahara;

- At the bottom were the tozama daimyō, who did not support the Tokugawa until during/after Sekigahara (some daimyo dramatically changed sides during the battle, but were still considered in this low tier).

For the next 250 years, fudai daimyō and their retainers received preferential treatment in government, received higher stipends, had better career opportunities, and so on, compared to the tozama daimyo and their retainers. Even when the Battle of Sekigahara was far gone from living memory, the timing of that simple change had ramifications.

I was reminded of this system a few days ago by meeting some recent Russian emigres.

Through my previous employer in Tokyo, I've worked closely with a number of Russians who had left the country in pursuit of a better life in Japan and beyond. I will readily admit that I was skeptical of my Russian colleagues at first. I had scarcely spent time with any Russians previously, and my image of Russians was informed by American entertainment media that often casts Russians as the bad guys, by real history of the Soviet Union and Russia as expansionist authoritarians, and by current events in which Putin's Russia was continuing that brutish and expansionist style.

Over time, though, I came to appreciate that few if any of my Russian acquaintances deserved such an association with their regime. Not only was it unfair to paint over an entire large country of people with a single dark brush, but the Russians I knew were actually self-selected to be especially unlike their regime. Many of my Russian colleagues (and, increasingly, friends) had left Russia at least in part because of the behavior of their own government at home and abroad.

Of course, being unhappy under an authoritarian regime does not automatically make one a passionate liberal democratic internationalist, but most of my colleagues were motivated by the desire to live in and expand a more open society.

The renewal of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 no doubt made many people reassess their attitudes toward Russia and Russians. Most of the Russians of my acquaintance were outraged by and deeply critical of the invasion; I saw one ex-Russian (she had recently renounced her Russian citizenship) at an anti-Putin rally in Tokyo. Some spoke of breaking ties with relatives back home who were too inculcated by the regime to see the situation clearly. Watching the news and listening to my friends talk about the insane nationalism back home made it clear these liberal sentiments were far from universal, though. If the preceding five years of getting closer with Russians had disabused me of my stereotype that all Russians were inherently shady characters, the invasion reminded me that some Russians really are bad.

This brings me back to meeting some young men who had left Russia just a few months ago. I was struck by my own reaction as I listened to them talk about leaving, and I realized how strong the underucrrent of judgment I carried was. If they were offended by the war, why not leave in February or March? If Putin's expansionism was so objectionable, why not leave in 2008 or 2014? If the authoritarianism was an outrage, why leave now?

The tight correspondence between when my new acquaintances had left Russia and when Russia had instituted conscription was not lost on me.

I realized that these men had done what I think is the right thing, but they'd done it at the wrong time, and in my mind, that was a strike against them. They had done the right thing eventually, but it seems that they waited until the cost-benefit tradeoff had gotten personally steep, rather when it was a principled stand. Half credit. Tozama emigres. Not like my friends, the fudai emigres.

Now, I hasten to add, this was my instinctual judgment, not a carefully considered position. Leaving one's country is costly and expensive; it's tied up in all sorts of personal factors I could never know about; it requires having a place to land; there's a reasonable enough argument that staying to use Voice rather than choosing Exit may be the benevolent thing to do. I am not saying that dividing people into these temporal categories is rational, morally justified, or correct.

All the same, the thought occurs.

So what?

The obvious question is, where is my timing off? What am I late to?

There are plenty of people who think that living comfortably in America, paying taxes, and so on, is an immoral act. They think I ought to put my body upon the gears in opposition to injustices perpetrated by my government. I don't think so, but it's not prima facie a wildly insane thing to think.

Personally, I'm almost certain that my eating of intelligent or social animals is immoral, but other than octopus (which I didn't enjoy that much anyway), I haven't been willing to take on the costs to convenience, social life, and hedonistic pleasure that would come from removing meat from my diet. While I doubt anyone will be relegated to a political second class for having eaten meat, I would not be at all surprised if my descendants will think I was a barbarian for participating in the needless suffering and slaughter of so many sentient creatures.

Many slaveholders knew that they would be judged by posterity for their moral failings; some found excuses in the "impracticality" and economic complexity of mass manumition, so they kicked the can down the road.

– Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia

Yet they went right on participating in slavery.

I'll be more surprised, though, to learn what attitudes of mine will offend posterity that I am not even aware of. Most liberals and moderates in the West now approve of gay marriage, and can countenance no other position on the issue as morally-defensible. Certainly, I am among them.

Yet, in most quarters the concept itself was inconceivable until only the most recent decades. George Washington, Abraham Licoln, and likely even Martin Lutker King, Jr., had no conscious position on gay marriage whatsoever. We can intuit what they would have thought, but despite all the conceptual building blocks (homosexual people and marriage) existing, most people never would have explicitly considered the morality of their overlap.

In what areas will I be seen as so out-of-touch by the future? What soon-to-be-obvious intersections will carry great obvious moral weight that I cannot imagine now?

I hope the future will be kind to us, rather than relegating us as too-late adopters of right thinking.